White people have controlled race relations in the United States for the last four hundred years. It is still a mess. It is time for white people to become honestly aware of the state of race in the United States today, acknowledge it with humility, and work to repair the broken systems underlying the inhumanity that still exists. These five books can be a start for that process.

We begin with Rhonda Magee’s The Inner Work of Racial Justice, which offers us optimism through its clear path forward. Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates and The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander tell the story of our broken world through a very personal and a broad institutional lens, respectively. The Princeton Fugitive Slave by Lolita Buckner Inniss demonstrates the critical importance of perspective taking, something required for anyone seeking to lead compassionately. Finally, White Fragility, by Robin DiAngelo helps us understand why it is so hard for white people to talk about racism.

Compassionate leadership starts with work on ourself and ends with a sense of connection to everyone through our shared common humanity. What we do to any one of us we are doing to all of us. Explore the wisdom in these books as a starting point to expand your understanding of systemic racism and lead with compassion and humanity.

The Inner Work of Racial Justice: Healing Ourselves and Transforming Our Communities Through Mindfulness

by Rhonda V. Magee

How do we live productively and peacefully in a world surrounded by people with vastly different backgrounds from our own? The entirety of human history, and not just recent weeks in the United States, does not offer much hope for our ability to accomplish this. Law professor Rhonda Magee does.

With book sections that progress from Grounding to Seeing to Being to Doing to Liberating, Magee shows us how to recognize the profound depth of our shared common humanity and to honor that which has historically divided and separated us: our particular differences. She offers hope that inner awareness and mindful practices can help us transform ourselves, and in so doing, transform the world that is so in need of healing right now.

Between the World and Me

by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Broadly proclaimed and awarded, Between the World and Me is patterned after James Baldwin’s A Fire Next Time. Although it is written as a letter to the author’s fifteen-year-old son, white leaders should listen carefully to Coates important closing words. “I do not believe we can stop them,… because they must ultimately stop themselves.” The “them” he is referring to are those he calls “Dreamers,” or those who believe in the American Dream of perfection and exceptionalism.

Coates doesn’t use racial terms because of their artificiality as a social construct, saying “race is the child of racism, not the father.” Make no mistake, those Dreamers who “must ultimately stop themselves” are those who consider themselves to be white. That is who has created this system of racism, and that is the only group who can upend the system.

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

by Michelle Alexander

The New Jim Crow is a tragic telling, with abundant statistical support, of the treatment of young black men by the American economic and criminal justice system. Alexander says that it has been intentionally written for people who care about racial justice. If after reading this book, one doesn’t care about racial justice, they couldn’t have been paying attention to what is written on the pages they read.

Alexander pulls no punches, naming names and pointing fingers when she believes it necessary. Don’t read this book expecting the fingers to be pointing at “them” – whoever you think they are. The fault can be seen to lie squarely at the reader’s feet, no matter who the reader happens to be.

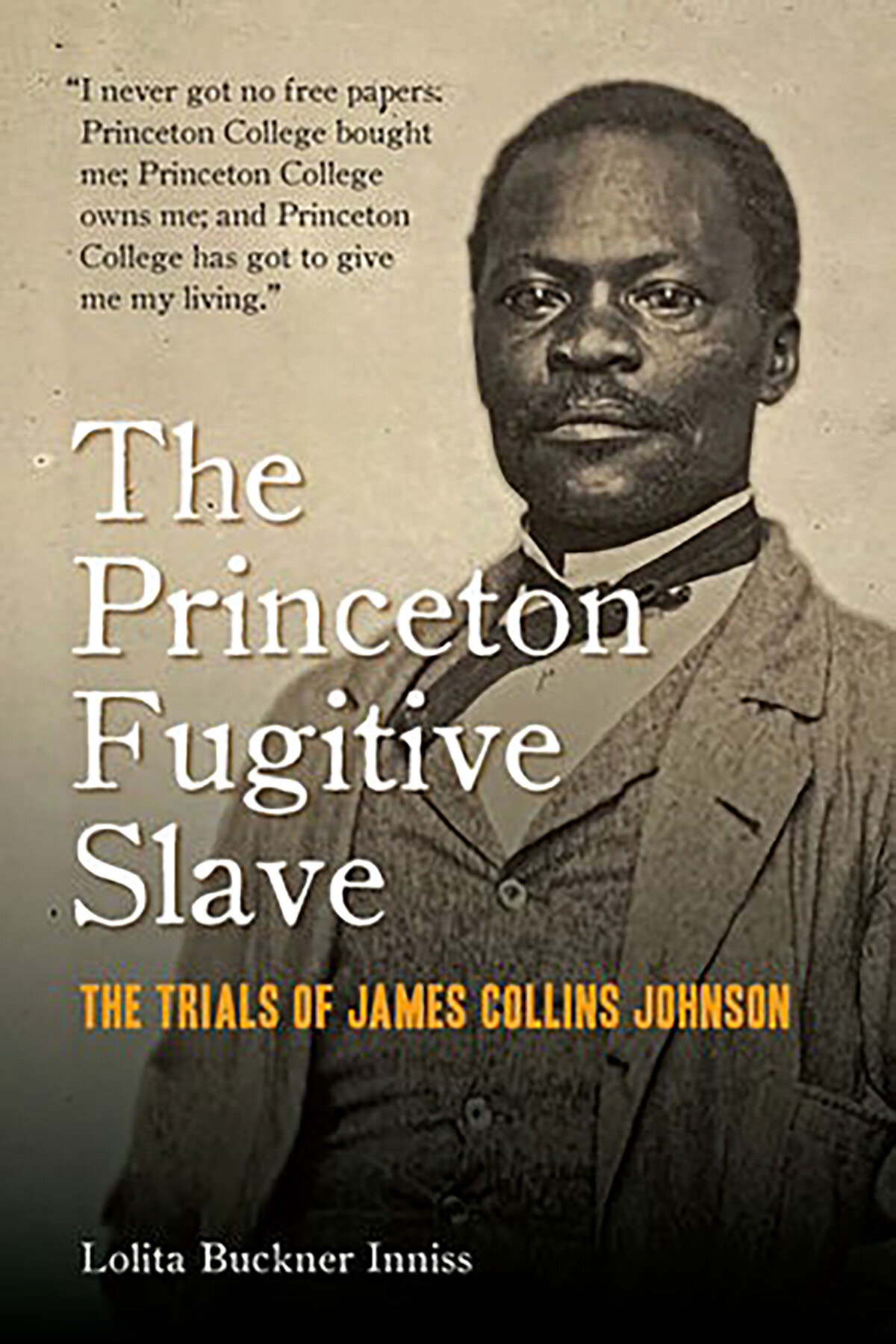

The Princeton Fugitive Slave: The Trials of James Collins Johnson

by Lolita Buckner Inniss

American history has largely been chronicled by white men, creating an excessively self-congratulatory view of the last 400 years. The Princeton Fugitive Slave is a painstakingly researched book (footnotes and bibliography run to nearly 100 pages), by SMU Law School professor Lolita Buckner Inniss, which tells the story of James Collins Johnson from his point of view.

In a highly readable narrative of the fascinating life of a man who escaped slavery in Maryland, was discovered in free New Jersey, arrested, and prepared to be sent back to his “owner,” then bought out of slavery by a resident of the town of Princeton, and became a fixture on the Princeton campus peddling food and candy from a cart.

Inniss has richly transformed Johnson’s story from that of an escapee from a “kind slave master,” saved by a white woman, and beloved by Princeton University students as a sweet, jovial darling into a much more nuanced portrait of a human being. Her portrayal raises important questions about what it means to be free, and where the line lies between work and servitude. Most of all it is a lesson in the critical importance in listening to the narrative of each person.

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism

by Robin DiAngelo

Science is clear that we are all prejudiced; that we all have biases deeply ingrained within us. Responding productively to them – in ways that help eliminate racial inequalities – requires us to acknowledge our biases and transform them. Yet, the cultural context for racism has become so binary that revealing even the slightest bit of bias can be untenable. Herein lies the Catch-22 of white fragility: we can’t create a better world without naming the biases we all have, but naming them creates an extraordinary fear among well-intentioned people of marginalization.

In White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, Robin DiAngelo examines the roots of the modern American racial structure and the reasons it is so difficult to acknowledge the pervasiveness of racial bias. She offers a path forward for white people to dismantle the grossly inequitable structure within which we all live.